Fundamentals

As a matter of fact, GNSS baseband signal processing requires a high computational load. Even in modern computers, real-time processing is hard to reach without a proper software architecture able to make the most of the processor(s) that are executing it. It is then of the utmost importance to exploit the underlying parallelisms in the processing platform executing the software receiver in order to meet real-time requirements.

A fundamental model of architectural parallelism is found in shared-memory parallel computers, which can work on several tasks at once, simply by parceling them out to the different processors, by executing multiple instruction streams in an interleaved way in a single processor (an approach known as simultaneous multithreading, or SMT), or by a combination of both strategies. SMT platforms, multicore machines, and shared-memory parallel computers all provide system support for the execution of multiple independent instruction streams, or threads. This approach is referred to as task parallelism, and it is well supported by the main programming languages, compilers, and operating systems. To make this potential performance gain effective, the software running on the platform must be written in such a way that it can spread its workload across multiple execution cores. Applications and operating systems that are written to support this feature are referred to as multi-threaded. When programmed with the appropriate design, execution can be accelerated almost linearly with the number of processing cores.

Hereafter, we describe the key underlying concepts and the software design on which GNSS-SDR is built upon.

A model for software-defined radios

Task parallelization focuses on distributing execution processes (threads) across different parallel computing nodes (processors), each executing a different thread (or process) on the same or different data. Spreading processing tasks along different threads must be carefully designed in order to avoid bottlenecks (either in the processing or in memory access) that can block the whole processing chain and prevent it from attaining real-time operation. This section provides an overview of the underlying key concepts and task scheduling strategy implemented in GNSS-SDR.

Theoretical foundations: Kahn’s process networks

The approach described hereafter is based on Gilles Kahn’s formal, mathematical representation of process networks1 and his efforts to define a language based on a clear semantics of process interaction which facilitates well-structured programming of dynamically evolving networks of processes2.

A Kahn process describes a model of computation where processes are connected by communication channels to form a network. Processes produce data elements or tokens and send them along a communication channel where they are consumed by the waiting destination process. Communication channels are the only method processes may use to exchange information. Kahn requires the execution of a process to be suspended when it attempts to get data from an empty input channel. A process may not, for example, test input for the presence or absence of data. At any given point, a process can be either enabled or blocked waiting for data on only one of its input channels: it cannot wait for data from more than one channel. Systems that obey Kahn’s mathematical model are determinate: the history of tokens produced on the communication channels does not depend on the execution order1. With a proper scheduling policy, it is possible to implement software-defined radio process networks holding two key properties:

- Non-termination: understood as an infinite running flow graph process without deadlocks situations, and

- Strictly bounded: the number of data elements buffered on the communication channels remains bounded for all possible execution orders.

An analysis of such process networks scheduling was provided in Parks’ PhD Thesis3.

Idea to take home: Software-defined radios can be represented as a flow graph of nodes. Each node represents a signal processing block, whereas links between nodes represent a flow of data. The concept of a flow graph can be viewed as an acyclic directional graph (i.e., with no closed cycles) with one or more source blocks (to insert samples into the flow graph), one or more sink blocks (to terminate or export samples from the flow graph), and any signal processing blocks in between.

An extremely simple flow graph would look like this:

Example of a very simple flow graph.

Example of a very simple flow graph.

and another more complex example that already should be familiar to you could be as:

Typical GNSS-SDR flow graph.

Typical GNSS-SDR flow graph.

Implementation: GNU Radio

An actual implementation of these concepts is found in GNU Radio, a free and open-source framework for software-defined radio applications. In addition to offering an extensive assortment of signal processing blocks (filters, synchronization elements, demodulators, decoders, and much more), GNU Radio also provides an implementation of a runtime scheduler meeting the requirements described above. This allows developers to focus on the implementation of the actual signal processing, instead of worrying about how to embed such processes in an efficient processing chain.

Idea to take home: By adopting GNU Radio’s signal processing framework, GNSS-SDR bases its software architecture in a well-established, highly-efficient design and an extensively proven implementation.

The diagram of a processing block (that is, of a given node in the flow graph), as implemented by the GNU Radio framework, is shown below:

Diagram of a signal processing block, as implemented by GNU Radio. Each block

has a completely independent scheduler running in its own execution thread and

an asynchronous messaging system for communication with other upstream and

downstream blocks. The actual signal processing is performed in the

Diagram of a signal processing block, as implemented by GNU Radio. Each block

has a completely independent scheduler running in its own execution thread and

an asynchronous messaging system for communication with other upstream and

downstream blocks. The actual signal processing is performed in the work()

method. Figure adapted from

these Johnathan Corgan’s slides.

Each block can have an arbitrary number of input and output ports for data and for asynchronous message passing with other blocks in the flow graph. In all software applications based on the GNU Radio framework, the underlying process scheduler passes items (i.e., units of data) from sources to sinks. For each block, the number of items it can process in a single iteration is dependent on how much space it has in its output buffer(s) and how many items are available on the input buffer(s). The larger that number is, the better in terms of efficiency (since the majority of the processing time is taken up with processing samples), but also the larger the latency that will be introduced by that block. On the contrary, the smaller the number of items per iteration, the larger the overhead that will be introduced by the scheduler.

Thus, there are some constraints and requirements in terms of the number of available items in the input buffers, and in the available space in the output buffer in order to make all the processing chain efficient. In GNU Radio, each block has a runtime scheduler that dynamically performs all those computations, using algorithms that attempt to optimize throughput, implementing a process network scheduling that fulfills the requirements described in Parks’ PhD Thesis3. A detailed description of the GNU Radio internal scheduler implementation (memory management, requirement computations, and other related algorithms and parameters) can be found in these Tom Rondeau’s slides.

Idea to take home: In this approach, each processing block executes in its own thread, trying to process data from their income buffer(s) as fast as they can, regardless of the input data rate. An underlying runtime scheduler is in charge of managing the flow of data through the flow graph from source(s) to sink(s).

Under this scheme, software-defined signal processing blocks read the available samples in their input memory buffer(s), process them as fast as they can, and place the result in the corresponding output memory buffer(s), each of them being executed in its own, independent thread. This strategy results in a software receiver that always attempts to process the input signal at the maximum processing capacity, since each block in the flow graph runs as fast as the processor, data flow and buffer space allow for, regardless of its input data rate. Achieving real-time is only a matter of executing the receiver’s full processing chain in a processing system powerful enough to sustain the required processing load, but it does not prevent from executing exactly the same process at a slower pace, for example, by reading samples from a file in a less powerful platform.

Software architecture in GNSS-SDR

After defining some basic notation, this section describes a software design based on object-oriented programming concepts that allows for the efficient implementation of software-defined GNSS receivers.

Notation

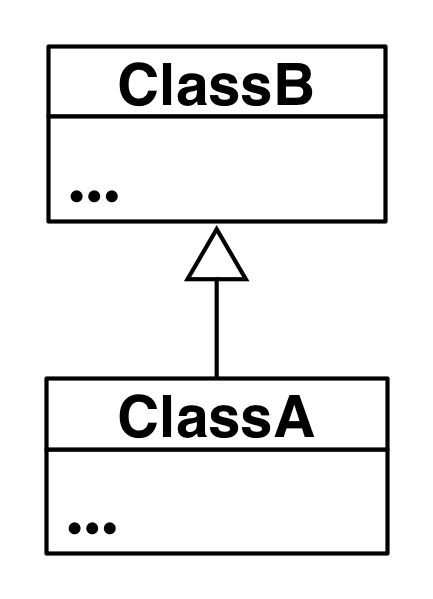

The notation is as follows: we use a very simplified version of the Unified Modeling Language (UML), a standardized general-purpose modeling language in the field of object-oriented software engineering. On this page, classes are described as rectangles with two sections: the top section for the name of the class, and the bottom section for the methods of the class.

A dashed arrow from ClassA to ClassB represents the dependency relationship.

This relationship simply means that ClassA somehow depends upon ClassB. In

C++ this almost always results in an #include.

ClassA depends on ClassB.

Inheritance models is a and is like relationships, enabling you to reuse

existing data and code easily. When ClassB inherits from ClassA, we say that

ClassB is the subclass of ClassA, and ClassA is the superclass (or parent

class) of ClassB. The UML modeling notation for inheritance is a line with a

closed arrowhead pointing from the subclass to the superclass.

ClassA inherits from ClassB.

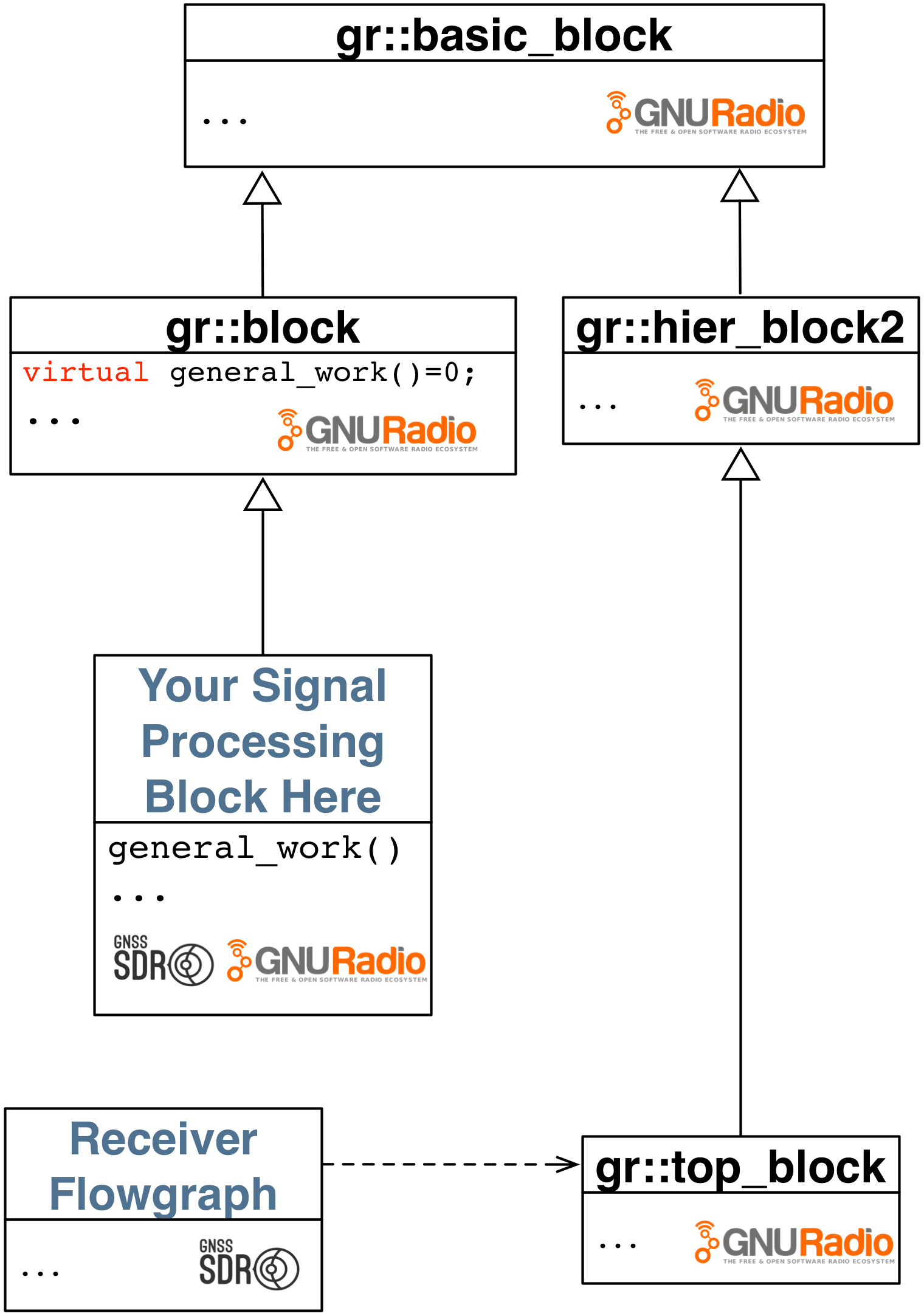

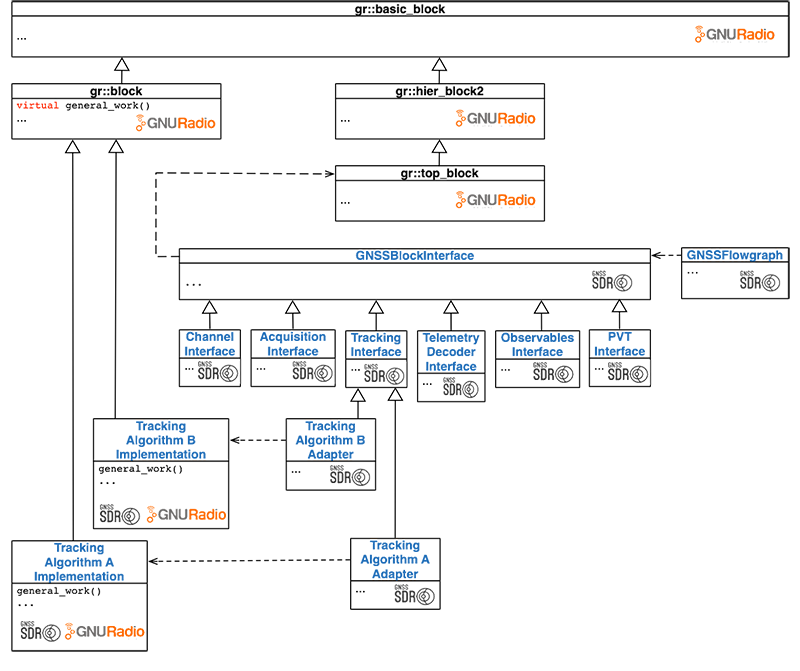

Class hierarchy overview

A key aspect of an object-oriented software design is how classes relate to each

other. In the GNU Radio framework,

gr::basic_block

is the abstract base class for all signal processing blocks, a bare abstraction

of an entity that has a name and a set of inputs and outputs. It is never

instantiated directly; rather, this is the abstract parent class of both

gr::hier_block2,

which is a recursive container that adds or removes processing or hierarchical

blocks to the internal graph, and

gr::block,

which is the abstract base class for all the processing blocks. A signal

processing flow is constructed by creating a tree of hierarchical blocks, which

at any level may also contain terminal nodes that actually implement signal

processing functions:

GNU Radio’s class hierarchy.

GNU Radio’s class hierarchy.

The class

gr::top_block

is the top-level hierarchical block representing a flow graph. It defines GNU

Radio runtime functions used during the execution of the program: run(),

start(), stop(), wait(), etc. It is used for defining the receiver

flow graph (that is, the interconnections within all the required blocks)

according to the configuration (more on that in the description of the Control

Plane).

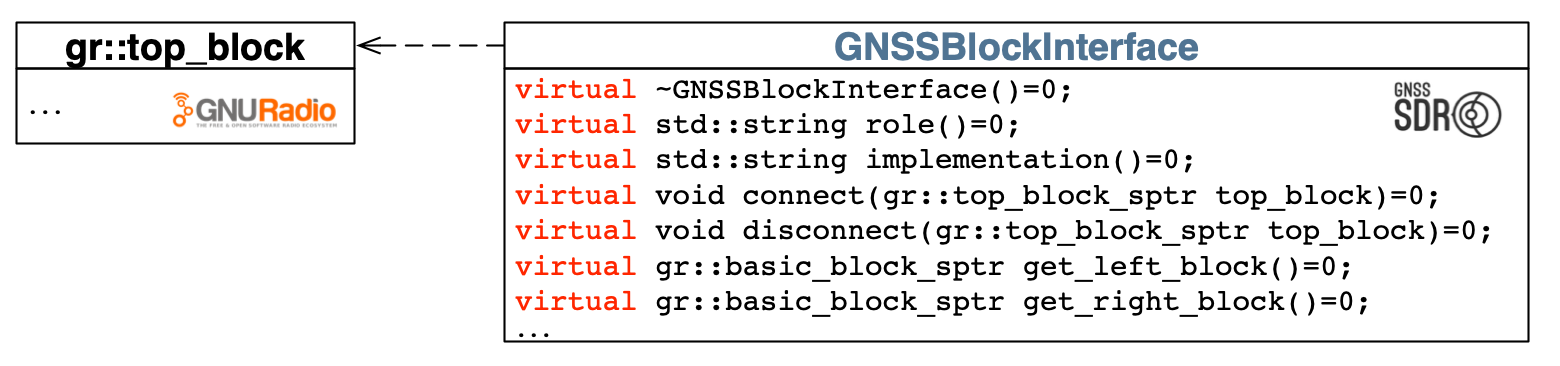

The class called

GNSSBlockInterface

is the common interface for all the GNSS-SDR modules. It defines pure

virtual methods, that are required to be implemented by a derived class.

Block interface for all Signal Processing blocks.

Block interface for all Signal Processing blocks.

Definition: Classes containing pure virtual methods are termed abstract; they cannot be instantiated directly, and a subclass of an abstract class can only be instantiated directly if all inherited pure virtual methods have been implemented by that class or a parent class.

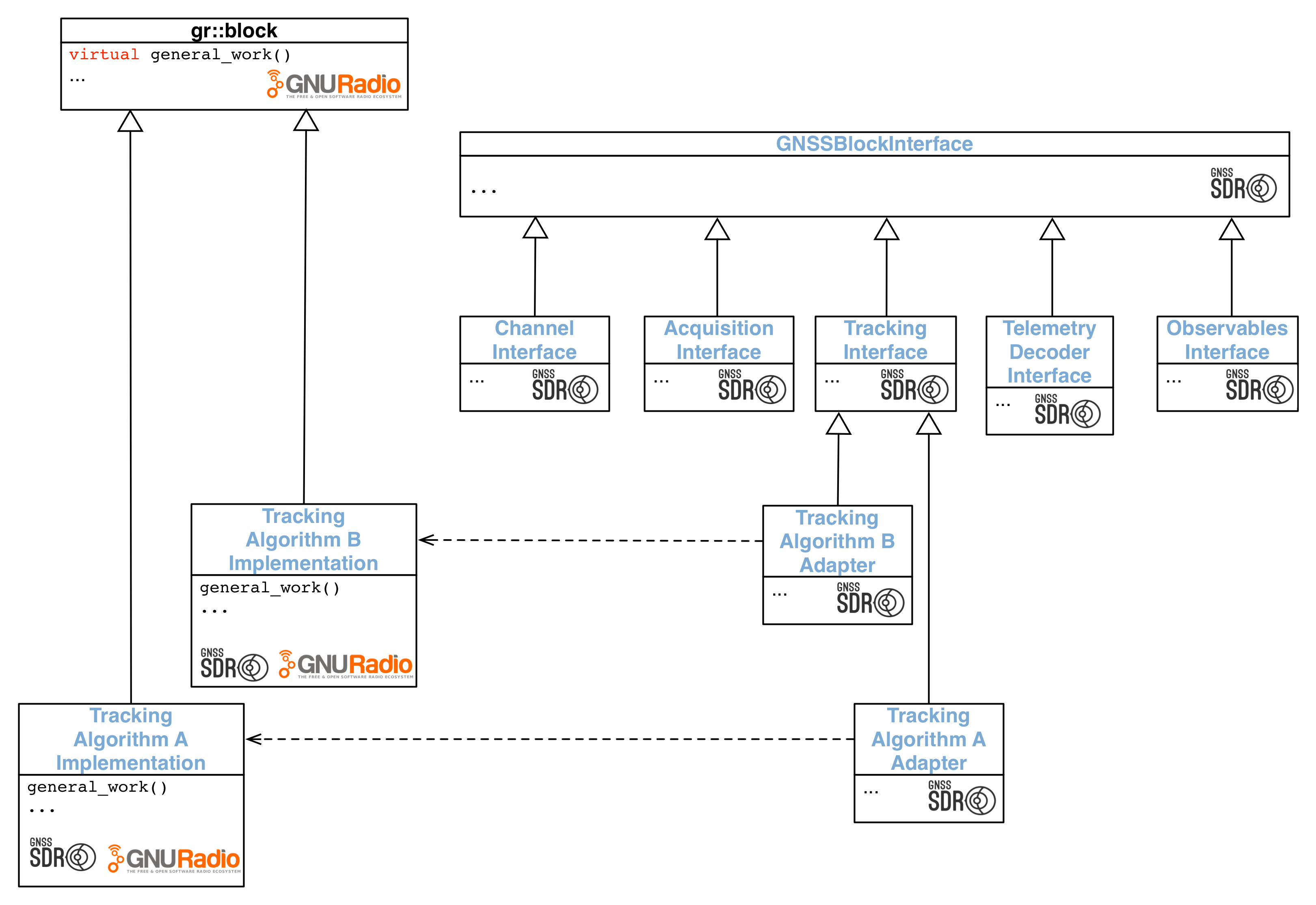

Subclassing

GNSSBlockInterface,

we defined interfaces for the receiver’s processing blocks. This hierarchy,

shown in the figure below, provides a way to define an arbitrary number of

algorithms and implementations for each processing block, which will be

instantiated according to the configuration. This strategy defines multiple

implementations sharing a common interface, achieving the objective of

decoupling interfaces from implementations: it defines a family of algorithms,

encapsulates each one, and makes them interchangeable. Hence, we let the

algorithm vary independently of the program that uses it.

Class hierarchy for the Signal Processing Plane.

Class hierarchy for the Signal Processing Plane.

This design pattern allows for an infinite number of algorithms and

implementations for each block. For instance, defining a new algorithm for

signal acquisition requires an adapter ensuring it meets a minimal

AcquisitionInterface,

and the actual implementation in form of GNU Radio processing block (that is,

inheriting from

gr::block).

Example: An available implementation of an Acquisition block is called

GPS_L1_CA_PCPS_Acquisition. Like any other Acquisition block, it has an adapter that

inherits from

AcquisitionInterface

and the corresponding GNU Radio block inheriting from

gr::block

and implementing the actual processing. You can take a look at the source code:

- Adapter interface: gnss-sdr/src/algorithms/acquisition/adapters/gps_l1_ca_pcps_acquisition.h

- Adapter implementation: gnss-sdr/src/algorithms/acquisition/adapters/gps_l1_ca_pcps_acquisition.cc

- Processing block interface: gnss-sdr/src/algorithms/acquisition/gnuradio_blocks/pcps_acquisition.h

- Processing block implementation: gnss-sdr/src/algorithms/acquisition/gnuradio_blocks/pcps_acquisition.cc

General class hierarchy for GNSS-SDR

The following figure summarizes the general class hierarchy for GNSS-SDR and its relation to the GNU Radio framework:

Overview of class hierarchy in GNSS-SDR and its relation to GNU Radio.

Overview of class hierarchy in GNSS-SDR and its relation to GNU Radio.

Up to this point, we have described a software design that accounts both for efficiency and scalability. Modeling the GNSS receiver as a flow graph of processing nodes with a source block delivering signal samples, a network of nodes reading from their input buffer(s) and writing the output at their outputs buffer(s), and a sink block, efficient process scheduling strategies can be put in place. Then, we have proposed a software architecture that builds upon the GNU Radio framework and defines interfaces for the key GNSS processing blocks. In addition, following this approach, we can define an unlimited number of implementations for each of the key GNSS signal processing blocks, all of them inheriting the underlying design and thus being easily reusable. For instance, we can define Acquisition implementations for GPS L1 C/A signals, Galileo E1B, and so on, and then use those blocks just as any other existing GNU Radio block, thus benefiting from nice features such as their internal runtime scheduler or the asynchronous message passing system. However, we still have not described how those blocks are connected together, how the whole system is managed, or how the user can configure those blocks in order to define a fully custom software-defined GNSS receiver. Those are jobs of the Control Plane.

References

-

G. Kahn, The semantics of a simple language for parallel programming, in Information processing, J. L. Rosenfeld, Ed., Stockholm, Sweden, Aug 1974, pp. 471–475, North Holland. ↩ ↩2

-

G. Kahn and D. B. MacQueen, Coroutines and networks of parallel processes, in Information processing, B. Gilchrist, Ed., Amsterdam, NE, 1977, pp. 993–998, North Holland. ↩

-

T. M. Parks, Bounded Scheduling of Process Networks, Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA, Dec. 1995. ↩ ↩2